Indonesia has revealed the final report on the crash of a Lion Air 737 Max jet in October 2018 that killed all 189 people on board. It crashed into the Java Sea 13 minutes after taking off from Jakarta, Indonesia. About five months after the crash, another 737 Max jet crashed just 6 minutes after taking off from Addis Ababa Bole International Airport in Ethiopia – killing 157 people.

The 353-page report from Indonesia’s National Transportation Safety Committee has put the biggest portion of the fault on the poor design of the Boeing 737 Max and a lack of regulatory oversight from the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). But the report also admits that the crash was caused by a series of failures committed by Boeing, Lion Air and pilots.

Indonesian air accident investigator Nurcahyo Utomo said – “From what we know, there are nine things that contributed to this accident. If one of the nine hadn’t occurred, maybe the accident wouldn’t have occurred.” The damning report zeroed in on the design of Boeing’s plane, highlighting flaws in its software system that continually pushed the plane’s nose down.

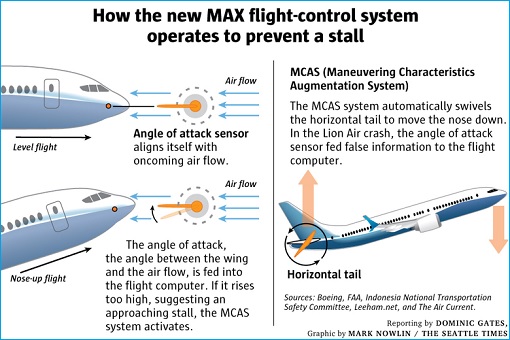

The report reveals how the problematic MCAS system had repeatedly forced the plane’s nose down, essentially forcing pilots to repeatedly apply 103 pounds of strength in an ultimately doomed attempt to control the plane. “The design and certification of the MCAS did not adequately consider the likelihood of loss of control of the aircraft” – concluded Indonesian regulators.

Boeing has acknowledged the problem with the MCAS – Manoeuvring Characteristics Augmentation System. To fit the Boeing Max’s larger, 14% more fuel-efficient engines, Boeing had to redesign the way it mounts engines on the 737. This change disrupted the plane’s centre of gravity and caused the Max to have a tendency to tip its nose upward during flight, increasing the likelihood of a stall.

The MCAS new software system was supposed to detect that in the event the nose is pointing up (or down) at a dangerous angle, it can automatically push the nose down in an effort to stop the plane from stalling. The report blames the crash on faulty “assumptions” made during the design and certification of the 737 Max about how the pilots would respond to malfunctions by the MCAS.

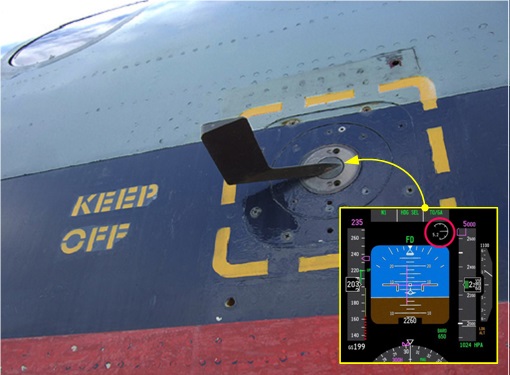

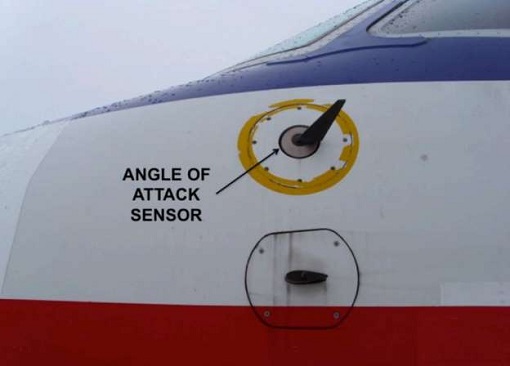

The software system had malfunctioned in the case of the Ethiopian Airlines and Lion Air. It was vulnerable because it relied on a single angle of attack (AOA) sensor. A fail-safe design concept should have a redundant system. On Oct. 28, the day before the crash flight, following a series of cockpit warnings about airspeed and altitude, a maintenance engineer installed a new angle of attack sensor.

Apparently, the Indonesian budget carrier Lion Air Flight 610 had recorded intermittent technical issues in the days leading up to the accident. Although the maintenance engineer was supposed to do an installation test to ensure the AOA sensor was correctly calibrated and installed, the maintenance records show no such test was performed.

The engineer did produce several photos of the flight display, which he claimed showed the test had been performed. But investigators could not confirm that the photos were indeed taken in the plane that crashed – raising suspicions. To make matters worse, the report also exposed a jaw-dropping discovery – 31 pages were missing from the aircraft’s October maintenance logs.

But the suspense didn’t end there. The replacement AOA sensor was actually a “second-hand” component, sourced from a certified aviation repair shop, Xtra Aerospace in Miramar, Florida. It’s unclear if it was to save money. The part was faulty, nevertheless. On the flight directly before the fatal flight, the replacement sensor was off by 21 degrees from the one on the other side of the plane.

The secondhand sensor had not been properly tested and was mis-calibrated by the shop. When the faulty sensor fed information to the plane’s MCAS system, it repeatedly pushes the plane’s nose down, leaving pilots fighting for control. On the Oct. 28 flight, the 21 degrees AOA sensor set off the same series of events that would show up again a day later on the accident flight.

Since Boeing hadn’t informed airlines or pilots about MCAS, the captain and his first officer didn’t understand what was happening. But they were lucky because a third pilot, another Lion Air first officer who was tagging along for the free ride, had stayed calm and found a way out of the situation. Cutting off electrical power to the tail had allowed them to regain control.

But instead of turning the plane around and landed as soon as possible, the pilot violated procedures and flew on to their destination. Upon landing, the captain reported only the issues that had shown up on his flight display. Fatally, he did not report the way the plane pushed the nose down or his use of the cut-out switches to resolve the problem – resulting in an “incomplete report.”

Had the maintenance engineer given the complete report, he would have had grounded the plane for further investigation due to the seriousness of the problem. To add salt into injury, the MCAS system takes readings from the two angles of attack sensors to determine how much the plane’s nose is pointing up or down – “angle of attack indicator” and “angle of attack disagree light.”

Unfortunately, the two safety features were not included in the aircraft by Boeing as standard safety features. Because of a software bug in the MCAS software, that light or indicator was working only on 737 MAXs where the airline had installed the separate optional feature. Lion Air hadn’t bought that option, unlike other “cash-rich” airlines in the United States.

As a result, the report concludes, the crew on Lion Air Flight 610 were “being denied valid information about abnormal conditions.” But the main flaw found was in the design of MCAS. It found that when Boeing engineers assessed possible failure scenarios, they assumed in its safety assessment that pilots would respond within 3 seconds to a system malfunction.

In the case of Lion Air, the report found that on both the previous flight, when the crew recovered control (partly thanks to luck that the three pilots managed to regain control through cut-off switches), and on the accident flight, when they did not (because the workaround solution wasn’t reported and communicated), it took both crews about 8 seconds to respond.

Boeing’s defective system together with a crew that lacked exceptional skill was the recipe for disaster on Lion Air Flight 610 on Oct 29. The first officer on flight 610, Harvino, a 41-year-old Indonesian, was not scheduled for the flight, but had been awakened at 4 a.m. with a schedule change. And the captain, 31-year-old Indian national Bhavye Suneja, told Harvino he had a bad flu.

Captain Bhavye was heard coughing 15 times in an hour on the cockpit voice recorder. The Indonesian investigators also found that off-duty pilot Harvino was not familiar with standard operating procedures (SOP) that were supposed to be memorized, and had performed poorly in some training exercises with the airline.

When the plane started showing various warnings on the display, Captain Bhavye Suneja asked Harvino to perform the Airspeed Unreliable checklist. Harvino had to be asked twice and even then, it took him four full minutes to find it in the Quick Reference Handbook (QRH). If he had done according to the checklist, autopilot would have had been engaged and MCAS is disabled.

The captain, busy combating the nose-down movements of the Boeing 737 Max, didn’t understand what was happening. He didn’t apply the cut-off switches. He wasn’t coordinating with Harvino as he fought the defective MCAS system. Then, perhaps because he wanted a break to think about what was wrong (or probably he was stressed), he “asked the first officer to take over the aircraft control for a while.”

The report notes that Captain Bhavye did not brief Harvino exactly what he needed to do when handing over control of the plane. The captain was probably struggling to understand what was wrong with the plane. There was no coordination or communication. Of course, Harvino, himself more clueless than the captain, quickly lost control and the plane plunged into the sea.

In short, the investigation report describes a catalogue of failures – from poor communication to bad design to inadequate flying skills – which contributed to the deaths of 189 people. There are lots of what-ifs in the chain of events leading to the crash. If the crew of the previous day’s flight had given a more detailed description of the problems they had faced, the plane might have been grounded.

Even if the plane was not grounded, the workaround solution of cut-off switches would provide useful tips to Captain Bhavye Suneja of the similar symptoms, even if he was hit with the flu and could not understand the problem at all. A more competent first officer could save the plane too, as he might pro-actively demand a briefing from the captain, which could spark a discussion as did the crew of the previous day’s flight.

Still, at the heart of that chain was MCAS – a new control system that the pilots didn’t know about, and which was vulnerable to a single sensor failure. Boeing – and worse, regulators FAA – allowed the system to be designed in this way and didn’t change it even after the Lion Air crash, leading to a further disaster on Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 (which killed 157 people on Mar 10, 2019).

Clearly, Boeing cannot point fingers elsewhere. A week ago, it was revealed that a transcript showing a top pilot, Mark Forkner, who played a central role in the development of the plane, had complained about the MCAS system in messages to a colleague in 2016, more than two years before the Boeing 737 Max was grounded because of the accidents.

The pilot said the MCAS was acting unpredictably in a flight simulator – “It’s running rampant. Granted, I suck at flying, but even this was egregious”. The messages were from November 2016, months before the Max was certified by the U.S. regulator FAA – suggesting a serious cover-up in Boeing, who has maintained that the Max was certified in accordance with all appropriate regulations.

As the chief technical pilot for the 737 Max, Mr. Forkner was in charge of communicating with the regulator FAA that determined how pilots would be trained before flying it. He helped Boeing convince international regulators that the Max was safe to fly. The best part was when he admitted in the message – “I basically lied to the regulators (unknowingly).”

Other Articles That May Interest You …

- More Problems – Now Boeing Is Forced To Suspend Test For New 777X Aircraft After “Door Explosion”

- An Admission Of Guilt – Former Boeing Official Invokes Fifth Amendment Protection In 737 MAX Scandal

- Boeing 737 MAX Has “No Value” – Lawyer Says Public Doesn’t Trust It, Client Can’t Use It

- Zero New Orders For 737 MAX – Airbus To Overtake Boeing As World’s Biggest Plane Maker

- It’s Not Over Yet – Lawsuits Are Piling Up Against Boeing For Misleading Investors & Covering Up

- How China Uses The Purchase Of 300 Airbus Jets To Pressure Both European Union & The U.S.

- Profit-Hungry Boeing – Crashed 737 Max Jets Did Not Have 2 Safety Features Because They’re Optional

- 3 Bailouts Involving RM30 Billion – Here’s Why Malaysia Airlines Should Be Shut Down Or Sold Off

- Secret Revealed – The Secret Chambers Where Pilot & Cabin Crew Rest & Sleep (Photos)

|

|

October 26th, 2019 by financetwitter

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Comments

Add your comment now.

Leave a Reply